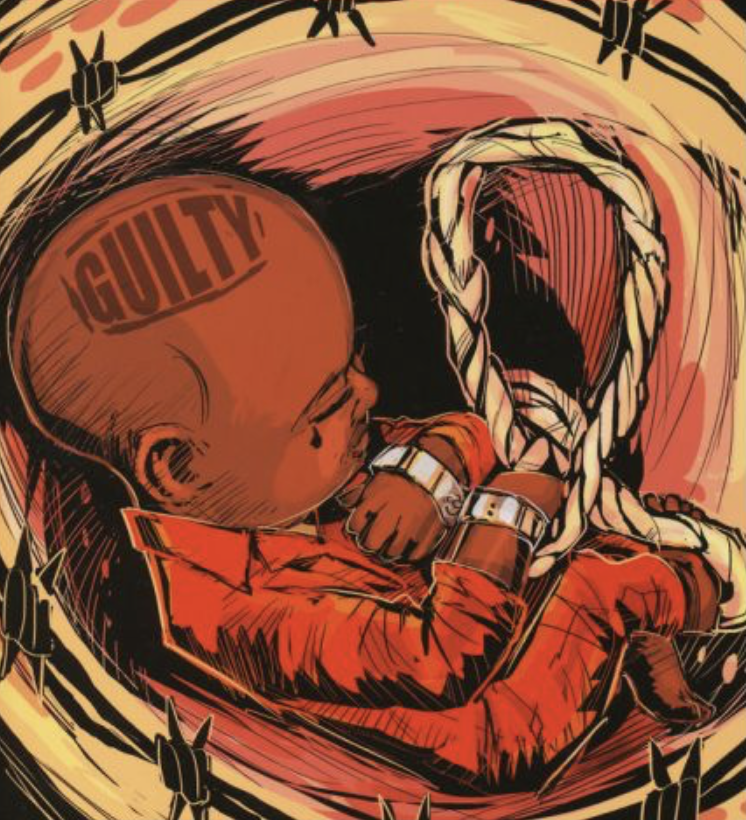

The uncovered truth is that the economic structure as we know it today is based on Industrialization. To upkeep such a progressive system, the exploitation of prison labor evolved to become essential. Ruth Wilson Gilmore coined the term prison fix, discussing how the increase in arrests and incarceration was a fix in order to solve social problems and how the operation of prisons aids the dehumanizing function of racial capitalism under mass incarceration. This matter has transcended to heavy criminalization and other fixes – such as the proposal of Cop City and increased racial systematic injustices. Within this paper, I will focus my topic of interest on the role of Black Women and Nonbinary people who are hyper-affected yet rarely represented coinciding with the law being used as a safeguard to revolutionize slavery into the modern day.

The Angela Davis text provides great recourse to uncover the placement Women truly hold within this “prison fix” capitalistic controlled world we live in. Davis is a long-standing feminist political activist and self-proclaimed revolutionary Marxist. To me, her text read as a direct humanitarian violation to (John) Locke’s philosophy, that Africana individuals now living in the United States are unable to self-govern, as their level of worth is the same as that of property. The concealment factor was that Black women were meant to take all responsibility for fieldwork and being at the hands of their slave masters for concubines or sex slaves while simultaneously caring for and birthing all children on the physical property they belonged to, including white children. Paralleled with the non-existent legal support– this model, reinforces the idealization of white supremacy as Law, as an entity one can not revolutionize as one way of “living” as opposed to the way – that it is. Davis portrays this as a dual dichotomy of being enslaved, physically in two opposing, intrusive, and confining ways whilst facing a steady decline of financial reassurances towards buying their freedom as compared to their Black male counterparts. Davis describes this dissonance as the Myth of the Black Matriarch, that the social position of the Black woman, is separated from their femininity which is rooted in whiteness and instrumentalized as a screen to deflect the operation of (white) male supremacy, evoking a patriarchal ideology.

What many fail to recognize is that for a true revolution, as Davis praises Fanon for noting, female participation is vital, she continues, “The status of woman in any given society is a barometer measuring the overall level of social development. As Fanon has masterfully shown, the strength and efficacy of social struggles – and especially revolutionary movement – bear an immediate relationship to the range and quality of female participation” Within her reflection, her overarching goal seems to be geared towards understanding the systematic position of the Black Woman and how that is not limited to the dimensions of Slavery but even adapted by foe and ally alike.

Though so vital to the system, Black women face multifaceted violence, the unjust treatment the womanly Being face in and out of prison paired with the subjectification of the Black body within the convict leasing system. This system longing from 1868-1908 is elaborated on in the documentary, Slavery by Another Name. This practice of the leasing system transcended into the prison industrial system through the reinforcement of the Thirteenth Amendment, marking that slavery was permissible if it was in the case of punishment for a crime, leading to incarceration or imprisonment. Later, began radical reconstruction as outlined in Slavery by Another Name, beginning with the establishment of the Fourteenth Amendment which gave Black men the right to vote, the hidden translation of this amendment was attempting to create a country without their being true equal citizenship; While simultaneously and purposefully removing women from that proposition, which alludes to women not only being degraded and exempt from unalienable rights of all peoples within the law but not given the right to change it.

The Documentary Prison in 12 Landscapes examines how incarcerations protrude beyond prison walls. From the atrocious minimum wage pay to the inhumane treatment of pregnant people within the prison bounds. The documentary introduces a variety of interview selections, the viewer is able to see how the overall economics of the penal system directly correlates to means of systematic/geographical oppression; As predicted in the woman with the trashcan lid violation, and how systems of systematic success coincide with individuals like with the White Attorney featured. The policing of Black encompassed neighborhoods, intentionally targeting people with little legal literacy structuralized the association of what constitutes someone as a criminal. That the system is creating them as opposed to finding them and inducing punishment accordingly. It’s an insightful documentary that uncovers the placement of prisons in the spaces we least expect.

I want to take this topic and authenticate it the creation of this Post Traumatic Slave System (hereafter; PTSS) that we spoke about in earlier weeks. Wihtin the Ida D. Wells text on lynching laws. With PTSS they can create a system that sends a purposeful message of fear and minimizes children’s success. Legally, lynching does not abide by US laws but its protruding constant existence, the assimilating patriotism and religion it enforces, and the economic benefits create a public display for repentions one must pay for defining the law of white supremacy. It instills a lingering feeling of control and surveillance that rids vicinities of Black joy and unwavering community and replaces it with the reinforcement of generational suffrage. As Wells mentions, the evil has been given another name.

White supremacy is the concurrent establishment of racial hierarchy and prestige that originated in slavery and its aftercomings. These fear-based relations stimulated by entities such as lynching laws and targeting policing structurally fortify its Lawfulness. Avant-Guade is demonstrated as leading a charge in unusual or experimental ideas – it is in direct opposition to the conventional world. Sexton’s article, The Avant-Garde of White Supremacy implies that this structurally uplifted and protected positioning of Whiteness is arbitrary in its direct relation to state violence. Sexton describes the police as a “vanguard of terror”, that those peoples and slave masters are innately two sides of the same coin, meant to perpetuate the same purpose. They are the initial holders of the Law of punishment and seemingly the most elite force of those who promote white supremacy. In order for this racial transgression to cease, we need a ‘new coin’ to reestablish the political force as upholders of empathy and ethical frameworks foremostly before racial terror.

From a philosophical and lawful standpoint – the grounds of white supremacy enforce a hegemonic world, despite the avant-garde elements that contradict its purpose and purity. In turn, it reinforces levels of personhood which, if to be accurately categorized, has white men on the top of the ladder and Black women at the bottom of its rankings. This racial personhood separation is structural and historically accumulative, both of these iterations reaffirm the Epistemology of Ignorance. This was coined within Charles W. Mills, Racial Contract, where he states,

“Correspondingly, the ‘consent’ expected of the white citizens is in part conceptualized as a consent, whether explicit or tacit, to the racial order, to white supremacy, wherecould be called Whiteness. To the extent that those phenotypically/genealogically/culturally categorized as white fail to live up to the civic and political responsibilities of Whiteness, they are in dereliction of their duties as citizens. From the inception, then, race is in no way an ‘afterthought’, a ‘deviation’ from ostensibility raceless Western ideals, but rather a central shaping constituent of those ideals.”

The establishment of implied racial segregation and staggeration marks that Western ( white ) ideals are exempt from moral accountability when compared to the ostracized communities of race, gender, and sexuality. This philosophical development sparked discourse on the inevitability factor of racial capitalism.

It creates a group polarization of law-backed entities like the police force and the victims of the violence like Black individuals. This sentiment aids in social genocide and degrading reputation of Black America, and again, reinforces whiteness as righteousness. Coexisting with the exposure of police violence only seems to intensify and expand the Prison Industrial Complex, relating the fear of racial terror to governmental structures and enforcing complacency. This current social and economic dissonance gap we currently experience is working, lawfully, exactly as planned, it is the collective awareness that they fear.

Continuing onward, Assata Shakur’s text titled Woman in Prison: How We Are exuberates the deterrence of normative gender roles in prison. Highlighting the Rikers Institute that is described as having “no criminals, only victims” prompted by the harsh conditions of these woman-born individuals. Rikers is the largest jail in New York City where Shakur spent time within – what is also known as Torture Island – bounds herself. The demographic of the jail holding eighty-five percent of its captives as pre-trail defendants eliminates their rights to human treatment, even before conviction or release. Within Shakur’s article, she exploits the validity of the guard’s playfully patronizing acts, stating; “To them, the women in prison are too stupid to stay out of jail”, this monolithic view of the woman creates an outlawed and degrading reality paired with little to no legal literacy. This revolutionized feelings of helplessness aid to an escapist culture, skewing these women towards immense drug use and self-destructive plea deals. With this, Shakur stresses the importance of sharing Black feminine voices; “It is imperative that we as Black women, talk about experiences that shaped us (because it is otherwise disregarded in history and modern silencing); that we access our strengths and weaknesses and define our own history.” Constant erasure and disinterest in (Black) women’s voices is what creates this political economy of a Slavish mindset, and thus evolve into this lingering animalistic reproduction viewing and treatment of Black women. Shakur is intimately indicating that to break the association of innate Black female inferiority, we must begin by telling our own stories.

All this is to say that whiteness is constituted by Black inferiority. The establishment of the Thirteenth Amendment solidifies the position of slaves within the convict lease system and is reinforced systematically by the Post Traumatic Slave System (PTSS) implications. The role of the Black and Nonbinary peoples role within slavery was historically diluted which coagulated its continual succession into the modern day. Within my paper, I used those facts to show the systematic recovery of slavery, prohibited by the law, and highlight the concealment of women’s voices and how its reinforced partner, the penal system, protrudes perpetually beyond prison walls.

Bibliography

Blackmon, Douglas A., 2008. Slavery By Another Name: The Re-enslavement of Black

Americans From the Civil War to World War II. New York, Doubleday.

Brett Story, The Prison in Twelve Landscapes. Social Justice/Global Options, 2016). Kanopy.

Davis, Angela. “Reflections on the Black Woman’s Role in the Community of Slaves,” in The Massachusetts Review (1972).

Gilmore, Ruthie. “Chapter Two: The California Political Economy,” Golden Gulag (University of California Press, 2007).

Mills, Charles W., 1997. The Racial Contract. Cornell University Press (Ithica and London).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Shakur, Assata. “Women in Prison: How We Are,” The Black Scholar7 (1978): B8-15

Wells, Ida B., “Lynch Law in America”. BlackPast.org. (2010, July 13). (1900) https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/1900-ida-b-wells-lynch-law-america/