To evaluate the validity and prevalence of race-thinking, I will be using the definition and implication as presented by Paul C. Taylor in his book, Race: A Philosophical Introduction (2013). Taylor defines race-thinking as “a way of assigning generic meaning to human bodies and bloodlines” (2013, p. 16) and racialism as the view that race-thinking is valid. While there is no doubt that race-thinking and racialism are very present throughout society, to say that the concept is valid or invalid requires clarification of the notion of validity. I believe validity can be viewed in two major ways: factual correctness, or what is bestowed as correct by a population. Race-thinking and categorization of peoples based on the observable features of their bodies, degrading human beings to the color of their skin or past of their bloodlines is inherently and morally wrong—in this way, I find it invalid under the guise of “correctness.” However, the prevalence and automatism of stereotypical categorization has made racialism societally understandable. The notion that race-thinking and categorization is an acceptable method for grouping individuals is institutionally validated throughout the social hierarchy. Racialism identifies a system of social organization that supposedly legitimizes social institutions. While I do not believe race-thinking is ethically valid and more likely serves as a tool to marginalize groups, I believe race-thinking exists so prominently in communities due to the following factors: humans have evolutionarily adapted to naturally categorize everything, and humans will use any disparity to create power structures. I will explain these phenomena with the support of Taylor’s metaphysical and genealogical analysis of race-thinking.

Taylor argues that race travels, asserting that who counts under what category is not universal, but the logic of category travels even if its specific application doesn’t. This is the result of a biological adaptation for most primates. Elliot Aronson, Timothy Wilson, and Samuel Sommers, authors of Social Psychology: Tenth Edition, explain, “The human mind cannot avoid creating categories, putting some people into one group based on certain characteristics and others into another group based on their different characteristics” (2019, p. 404-405). Researchers in the field of social neuroscience find that “creating categories is an adaptive mechanism, one built into the human brain” (Aronson et al., 2019, p. 404). Humans learn to categorize people and things from birth to maximize fitness and minimize potential harm. If a child were to be presented with a white dog that terrified or threatened them, it would be evolutionarily beneficial to avoid all white things of the same relative size and shape. This simple principle can be applied to common stereotypes and racial associations: a white woman sees a black man is wanted for rape in the media, she is made to be afraid of black men; we use Aunt Jemima syrup on our pancakes, subconsciously registering the matronly black woman stereotype. These generalizations are considered valid as society has deemed the categorization of race-thinking logical, although there is no true biological referent. In my opinion, these projections are invalid as they are essentially immoral and unfounded. Taylor maintains that because these stereotypes are so ingrained within society and our understanding of others, we must actively seek to unlearn these associations if we want to grow philosophically and morally. I would agree with this sentiment, as individuals with the least discriminatory interpretations of others are those that have been exposed to a variety of races, classes, and ideas so as not to afford one character to an entire race. Although perhaps evolutionarily beneficial, attributing character to race creates a greater social divide and perpetuates an “us versus them” mentality.

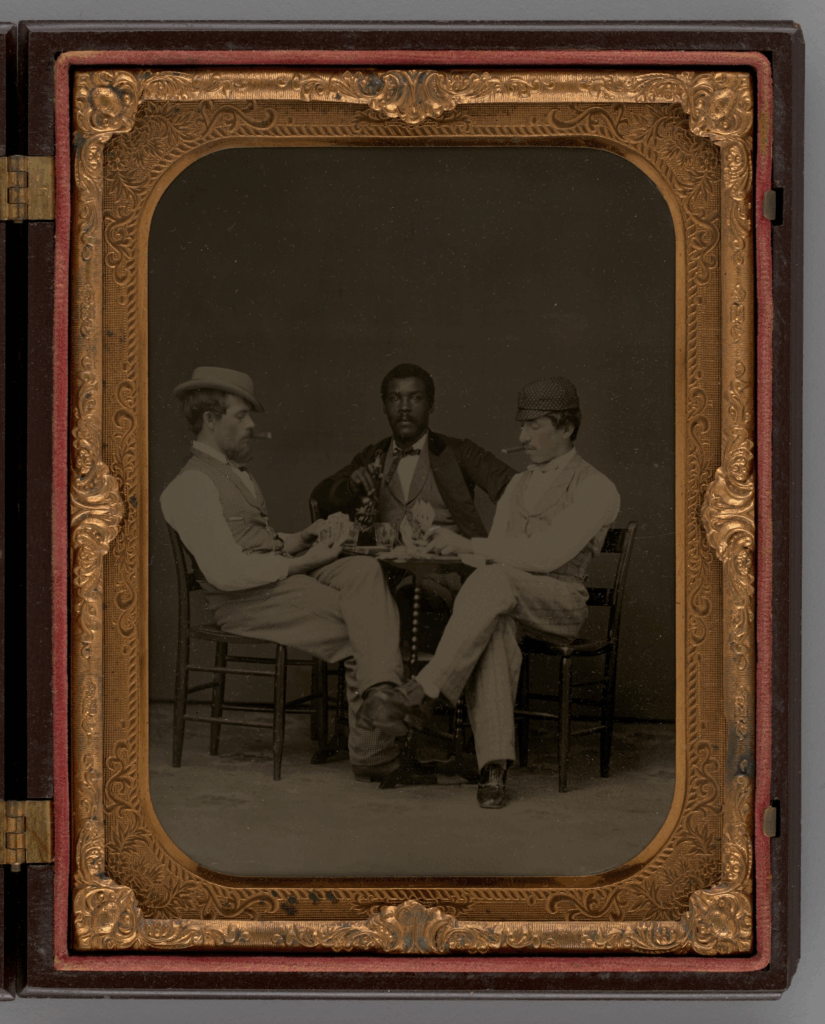

Associating stereotypes to traits allows for active discrimination throughout power structures. As nature seeks to differentiate itself within the margins of humanity, individuals use the divide to promote hatred and exclusion in an attempt to gain monetary, political, or social power. Taylor himself highlights the ways in which race is ingrained in social structures and is not simply a matter of individual attitudes. He calls attention to this targeted inequity, saying, “Our mainstream political discourse tends to focus on discrimination and squandered potential, underemphasizing the first, overemphasizing the second; and it leaves little room for structural analyses of how impersonal social processes systematically but indirectly disadvantage certain people” (Taylor, 2013, p. 83). Colonialism is arguably the strongest driver of the maintenance of racial categories and Taylor devotes a significant segment of his book to analyzing how colonialism continues to shape Western culture. The belief that European cultures are superior and any other civilization is subject to conquest, exploitation, and subjugation of people believed to be “primitive” or “uncivilized” continues to shape how people of color are treated in predominantly white societies. The history of white supremacy cannot be ignored in evaluating how class structures changed with the evolution of race-thinking. Hate crimes today feed off this hierarchical mindset that advocates for the discrimination of people of color based on negative stereotypes. While these dominance hierarchies should not be based on bloodline, it is societally understood and validated that people of color are disadvantaged by engrained race-thinking.

As a person who was raised in a conservative environment, I have firsthand experience of seeing race-thinking societally validated, and it has taken active unlearning and listening to try and understand what race-thinking looks like today. Understanding microaggressions and their significance can help us understand the greater perception of race. Coming to college as well as growing up with social media has exposed me to people from all different backgrounds and allowed me to appreciate the uniquity of individualism. While I am nowhere near perfect and may fall victim to the product of naturalized categorization and hierarchical structurization, Taylor’s principle of restructuring strongly rooted beliefs rings true in my personal acknowledgment of race relations and how I am perceived in society. I do not believe race-thinking is valid, however, I think its roots have been validated in society and needs to be combated with unlearning stereotypes in a movement towards human equity.

References

Aronson, E., Wilson, T. D., & Sommers, S. R. (2019). Prejudice: Causes, Consequences, and Cures. In Social Psychology (10th ed., pp. 402–439). Pearson.

Taylor, P. C. (2013). What Race-Thinking Is. In Race: A Philosophical Introduction (2nd ed., pp. 1–26). Polity Press.