Throughout the various works in political philosophy, the question of sovereignty has always been central in the discussion of the foundation of the state and its legal norms, from the stipulation of the social contract and the state of nature to the discussion of exploitation and domination in modern society. In Carl Schmitt’s Political Theology, he uses classical notions of sovereignty to critique liberal idealism and its legal norms through the concept of a state of exception, in which even the most liberal and democratic government must use its sovereign powers to override the supposedly universal rule of law. On the other hand, Michel Foucault diverges from the classical notions of sovereignty in his theories of biopower and biopolitics, and how modern states have evolved away from the usage of direct violence and towards a subtler form of control through various mechanisms and technologies in society. Although Schmitt and Foucault both critique classical liberalism and its legal norms, they argue from radically different perspectives and with fundamentally conflicting concepts of governance; however, it proves useful to compare these two critiques and analyze their differences. Particularly, it is prudent to theorize on how Schmitt’s notion of the state of exception can be reconceptualized in the context of Foucault’s postulations of biopower and biopolitics, and in-so-doing perhaps seek to reconcile their conflicting ideas of sovereignty as the power to decide the state of exception as opposed to the power to make live or let die.

The State of Exception as a Critique of Legal Norms

The central thesis of Schmitt’s problematization of legal norms comes from the classical notion of sovereignty as being inherently above the power of the law. Specifically, he seeks to critique the concept of classical liberalism as outlined by John Locke in his seminal work, The Second Treatise of Government, wherein the idea that the sovereign must be equal to its subjects under the rule of law is central. Locke scathingly critiques what he refers to as tyranny, the political situation in which a monarch—or any central authority figure—has the power to dominate their subjects through the laws of the land without being held accountable to those same laws. However, as Schmitt points out, even in liberal societies inspired by Locke’s treatises of government, there are certain situations where the law must be suspended for some reason or another: for instance, wartime liberal governments might institute certain measures such as mandatory conscription, manufacturing regulations, and sedition acts, or in the case of pandemics, wherein a government might instill quarantine measures, vaccine mandates, etc. Schmitt calls such situations a state of exception, when a liberal government which normally must follow its own laws can suspend them to enact and enforce authoritarian measures to address an exceptional situation such as any of the above. Therefore, in Locke’s social contract, although the sovereign and the commonwealth both agree to be subject to the law, it is specifically the sovereign which can and truly must reserve the right to suspend it in times of emergencies or crises. In particular, no individual subject of that society who is not the sovereign has the right to implement a state of exception to the rule of law, for obvious reasons—at least, no individual’s attempt to do so would be recognized as legitimate or having any authority whatsoever. It is a unique power which is reserved for the sovereign, so much so that Schmitt proposes it to be the defining feature of sovereignty, claiming, the “…sovereign is he who decides on the exception” (Schmitt, 1922, Political Theology, p. 1). This seemingly simple and frankly uncontroversial concept of sovereignty poses a fatal problem to the legal norms of classical liberalism, rendering them malleable, circumstantial, and ultimately subject to the will of the sovereign. As a result of this fact, despite Locke’s critique of tyranny, it seems inevitable that even in the most liberal of societies the sovereign still holds this special power to override the law, and as Schmitt rightfully observes, once it has done so it need not relinquish its authority; although a liberal society can institute a temporary authoritarian state of exception and then return to its previous state of liberalism, it is not compelled to, and certainly not by its own, clearly malleable laws.

One example of a contemporary and national institution of a state of exception can be observed in the U.S.A.’s implementation of the Patriot Act, and the various sub-policies which accompanied it, as Giorgio Agamben discusses in his work, State of Exception. Following the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, the American government essentially declared a national security crisis and instituted a series of counter-terrorist policies under the umbrella of a broader, more abstract “war on terror.” In a Schmittian sense, the government utilized the security crisis triggered by the terrorist attacks in order to exercise its sovereign power to operate above the law by instituting a state of exception. Many critics of U.S.A.’s counter-terrorist policies point out, for instance, that the policies of “‘indefinite detention’ and trial by ‘military commissions’… of noncitizens suspected of involvement in terrorist activities” (Agamben, 2005 State of Exception, p. 3) directly violate the principles of habeas corpus, the fourth, fifth, and sixth amendment rights of the constitution, as well as the standards expected in the treatment of prisoners of war as outlined in the Geneva conventions. However, in Schmitt’s critique of those very legal norms which the government violates in their treatment of terrorist detainees he points out that they can be violated when a state of exception is instituted, as was done in the symbolic and governmental declaration of the war on terror. In fact, many of these policies were popular amongst the American people insofar as they were deemed a necessary response to the clear aggression of terrorist groups; the aforementioned critics then, especially during the moment of crisis, were largely shunned as being unpatriotic, un-American, and even likened to terrorists themselves. From this fact emerges what Schmitt points out to be a fundamental contradiction of liberal society, that being the dichotomy of the idealistic legal norms which it purports and the necessity to violate them in times of need such as crises and emergencies. Then in Agamben’s interpretation of Schmitt’s state of exception, the passing of the Patriot Act as a response to the security crisis produced by the threat of terrorism seems to perfectly encapsulate the concept of the state of exception and how this brings out the inherent problem and contradiction of legal norms.

Additionally, another more recent example of a state of exception might be found in the COVID-19 pandemic and the government response to it. The extreme contagiousness of the virus caused a global pandemic which forced governments around the world—liberal, democratic, authoritarian, and otherwise—to respond with various authoritarian measures such as quarantines, curfew, social distancing, and mask and vaccine mandates. While the various policies aimed at curtailing the spread of the virus were clearly a necessary response to the emergent crisis, many critics of them were nonetheless correct in pointing out the multitude of ways in which they contradicted principles of bodily autonomy and freedom of movement generally regarded as legal norms in democratic society. Furthermore, in many ways those legal norms which conflicted with the necessary policy action to mitigate the effects of COVID-19 hampered the ability of particular nations such as the U.S.A. to respond to the crisis, as the institutions of checks and balances as well as the public backlash and resistance by representatives in the government largely acted to slow and weaken the enactment of said policies. As a thinker such as Schmitt might point out, many governments with stronger, more authoritarian systems which don’t abide by these same legal norms generally were certainly more capable and effective in their responses, whether it be in the number of COVID-19 cases or resulting deaths. One could argue here that because the powers of authoritarian governments are not strictly held back by the obligation to abide by certain legal norms, they were able to enact and enforce preventative policies far more efficiently and effectively than liberal democratic institutions. For Schmitt, such instances reveal a critical problem with legal norms and liberal societies, and why authoritarian regimes might be more consistent and capable, especially in times of need such as in the case of crises like the pandemic or terrorist attacks.

Through this line of reasoning, Schmitt argues that liberal societies posture themselves as bastions of freedom and equality, and furthermore as entirely different from authoritarian or monarchical societies, when in reality they are no different, as at any moment the sovereign still has the power to override the rule of law. Even the ideal liberal society is no different than a despotic monarchy, insofar as it is just as illogical to claim that liberalism upholds legal norms simply because they do so in times of peace as it would be to claim that monarchies operate in the best interest of the subjects simply because the current king in power happens to be a benevolent ruler. In reality, the idea of legal norms and inalienable rights under a liberal order is nothing more than an illusion, as when push comes to shove those very same governments have the power to suspend those rights and consequently violate them without recourse. For this reason, Schmitt entirely rejects the notion of legal norms and the supremacy of the rule of law, and instead embraces the necessarily authoritarian nature of the sovereign state. There is no better example of his critique than his own Nazi Germany, wherein economic depression following World War I created the conditions for a crisis which justified a suspension of the democratic and liberal legal order that would allow Hitler to reign over Germany with the full power of a dictator, despite his being democratically elected. Where this critique falls short however is in its failure to describe any difference in the employment of violence and power in liberal democracy as opposed to authoritarian and monarchical regimes; although Schmitt argues there is no such difference, it seems a false equivalency, as although it might be true that when push comes to shove a liberal society must employ authoritarian measures, this does not account for how radically different life under liberal democracy is in comparison to authoritarian regimes, and the many cases in which democratic societies do recover their liberalism after a state of exception. Although it is true that legal norms can be suspended by the sovereign state, there is no explanation for why the sovereign does (or doesn’t) abide by these norms prior to and after the state of exception. Although Schmitt does say that the state of exception is what is of interest, stating that “The exception is more interesting than the rule. The rule proves nothing; the exception proves everything…” (1922, p. 15) it seems shortsighted to set aside the lived experiences of subjects under liberal democracy. In particular, Schmitt’s critique of legal norms does not adequately address how society typically functions under liberal democratic institutions outside of the instances of emergency and crises, and why the government is often willing to relinquish its power following a state of exception.

Biopower as a Critique of Schmitt’s State of Exception

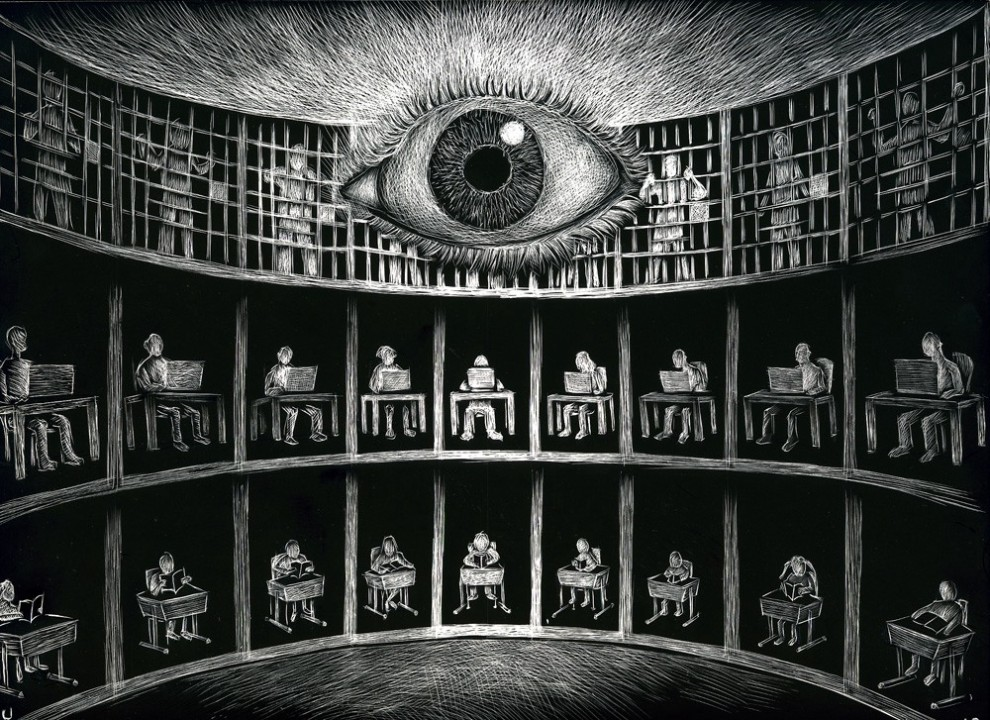

It is here where Foucault’s concept of biopower and biopolitics can be introduced to analyze the systems and functions of liberal democracies and how they differ from more classical formulations of sovereign states in cases such as monarchies or other authoritarian forms of government. In classical notions of sovereignty, the power of the government comes from its sovereign power “to take life or let live” (Foucault, 1976, Society Must Be Defended, p. 241), but in contemporary Western society, Foucault argues, the government exercises its power in the opposite way; politics is predicated not on the threat of death or exile but rather on the ability of the state “to make live or let die” (1976, p. 241). It is this very ability, defined by the state granting political life to some while subjecting others to bare life, which Foucault dubs biopower. This form of power can be exemplified by the treatment of homeless people here in America.

The state does not, at the institutional level, aim to eradicate, brutalize, or arrest homeless people; one is free to be homeless without direct interference from the government. But at the same time the homeless are excluded from political society, ostracized, denied the right to vote, and redirected to homeless encampments and treatment programs. Although the homeless are allowed to sleep out on the street, the state responds by putting spikes down on park benches, shutting down bridges and overpasses, and any other form of shelter, and tearing down any structures used by homeless people. Through these various exclusionary methods of the state, homeless people are subjected to bare life, alienated from the political world, and robbed of any functional means of securing their own supposedly inalienable rights. Furthermore, in the context of liberal democracies the presence of homelessness serves a particular biopolitical function insofar as homeless people act as cautionary tales for the general population to warn them of what they could become if they don’t work hard enough. Through this, the threat of being reduced to bare life at any moment is omnipresent in society, without the government ever having to make this threat explicitly, thus influencing people to follow certain norms of being a good worker without recognizing the institution of control that makes them do so. In this way the state exercises its power through biopolitical mechanisms which seek to control the lives of members of society through the threat of relegating them to the status of bare life: not part of the political society or economy, but paradoxically existing beside it.

Immediately Foucault’s thesis that the state now operates through biopower rather than through more direct forms of violent control diverges from the classical notion of sovereignty and the state as being the centralization and concentration of violence into the governmental apparatus which acts as a starting point for Schmitt’s argument. Instead, within a biopolitical paradigm of governance, power is decentralized and indirect, exercised in the form of biopower as defined by the state’s right to make live and let die, as opposed to the traditional forms of disciplinary power exemplified by capital punishment or exile, broadly characterized by the opposite refrain, make die or let live. In this sense Foucault might differentiate between the traditional authoritarian form of government which Carl Schmitt recognizes and the Western liberal democracies insofar as they wield their sovereign power in wildly different ways. Where an authoritarian country might institute concentration camps and gulags to punish and brutalize particular undesirables and minority groups, a liberal society constructs mechanisms of oppression which subtly operate behind the veil of objective law and disinterested bureaucracies to systematically segregate and subjugate certain marginalized groups, such as homeless people in American society. As Anatole France puts it, “The law, in its majestic equality, forbids rich and poor alike to sleep under bridges, to beg in the streets, and to steal their bread” (France, 1894, The Red Lily, p. 95). Furthermore, this difference implies that the exercise of sovereign power within the duration of a state of exception in liberal democracies will not reduce them to traditional authoritarian measures of direct violence but will emphasize the utilization of the various biopolitical bureaucracies of modern society to control its subjects. However, this consideration of a biopolitical state of exception would imply a grand departure from Schmitt’s initial conception in the context of classical sovereignty, and thus raises a question of how one might use the theory of biopower to analyze certain instances of states of exception.

Returning to the examples of the war on terror and the COVID-19 pandemic, it is interesting to analyze the policies and actions of the state in response to these crises through the lens of biopower, and how Foucault ultimately disagrees with how Schmitt might evaluate the actions of government under these circumstances. The evolution of state control into the form of biopower reveals the policies put forth by a government in a state of exception as implementations of new mechanisms of control over the population in order to preserve the state. This differs from Schmitt’s view in that although Schmitt is a cynical critic of liberal governments, he retains the notion that the sovereign acts in the interest of the whole of society—the subjects and the government—from classical theories of sovereignty and social contract. On the other hand, in the biopolitical function of the state of exception, policies such as the expansion of surveillance of the American population are not merely an invasion of privacy to protect the country from terrorists, but also self-preserving tactics taken on by the government to protect its own systems of power, sometimes contrary to the interests of the citizenry. Furthermore, the truth regime established by various apparatuses of the liberal order—those being the media, government, academia, education, etc.—assisted in the production of propaganda in the name of the war on terror, by solidifying an “us versus them” mentality. Although not an enforced policy, an understanding of biopolitical means of control through propaganda explains the effect that anyone who speaks out against the actions of the U.S.A. in regards to counter-terrorism is thus cast as an enemy, traitor, and even terrorist themselves. Additionally, Foucault might critique the notion that any of the policies enacted under the Patriot Act actually contradict the legal norms of liberalism, and that instead they are clearly a function of those norms. Take the treatment of suspected terrorist detainees by the American government for instance; technically speaking these people are not benefactors of constitutional rights insofar as they are not citizens of the U.S.A., and nor are they protected by the Geneva Convention in the precise legal sense, as they are not considered prisoners of war because they are members of terrorist organizations which are considered distinct from militaries or countries. While these justifications still seem to disagree with the spirit of liberal legal norms and rights, Foucault would point out that they are only possible because of the structure and rule of those legal norms; specifically, legal norms are a function of state control in the biopolitical sense, and it is no accident or coincidence that they allow the government to act in this way. Lastly, in the modern form of government the state of exception is no longer an isolated event or moment, but an ongoing process and function in the mechanisms of state control. For instance, the so-called war on terror and the Patriot Act, while framed as a particular event or temporary measure, have become regular features of American society and governance for the past 22 years, and one could even argue that it began far before that. In this sense the exception is illusory, and in fact the exception becomes the norm.

Perhaps an even better and more textual example of this evolution of crises and emergencies, which accompany the emergence of biopower and biopolitical regimes according to Foucault, can be observed in the COVID-19 pandemic. In his description of the evolution of epidemics to endemics, he claimed that “Death was no longer something that suddenly swooped down on life—as in an epidemic. Death was now something permanent, something that slips into life, perpetually gnaws at it, diminishes it and weakens it” (1976, p. 244). With the most recent pandemic, it’s obvious to see how this sentiment holds true; although the coronavirus was dangerous, its threat came not as the presence of imminent death as in, for instance, the Black Death in Medieval times, but in the form of illness, fatigue, separation, and perhaps most importantly, as a socio-economic threat. This exact point is reflected in Foucault’s claim that;

“It was not epidemics that were the issue, but something else—what might broadly be called endemics, or in other words, the form, nature, extension, duration, and intensity of the illnesses prevalent in a population. These were illnesses that were difficult to eradicate and that were not regarded as epidemics that caused more frequent deaths, but as permanent factors which—and that is how they were dealt with—sapped the population’s strength, shortened the working week, wasted energy, and cost money, both because they led to a fall in production and because treating them was expensive.” (1976, p. 244)

This effect or evolution of the way society relates to widespread illness largely comes from the advancement of medical technologies and their capability to address diseases as they appear, but at the same time they do not eliminate the disease in question, but rather construct systems to continually address them, as exemplified in the continual renewal of flu vaccinations, and the production of booster shots designed to address the new strands COVID-19 as they arise. Because there is no end to the pandemic in this technical sense it can be argued that there is also no strict end to the state of exception implemented in response to it, and that instead the policies which saw their extremes at the moment of crisis are reintegrated into the normal juridical model of government, acting as precedent for the inevitable next pandemic. In other words, the exceptional moment of crisis becomes a permanent fixture of the society henceforth: the fear of infection, the facial masks, the medicalization of our bodies, and the potential necessity of future quarantine. It is here where the analogy to the war on terror can be made clear, as with both pandemics and wars Foucault problematizes the conceptualization of them as singular crises or exceptional emergencies—as is done in Schmitt’s articulation of a state of exception—and instead understands them as fundamental to the proceeds of biopolitical functions of control in liberal democratic states.

Thus, under Foucault’s biopolitical paradigm of governance the instances of terror and pandemics are not isolated crises or emergencies, but merely manifestations of the biopolitical processes of securitization and medicalization in the operations of the state. Instead, the exception becomes the norm, and thus each state of exception becomes reintegrated into society and lasts far beyond the purview of the crisis; not in the classical authoritarian sense but rather through functions of biopolitical control made possible by the very legal norms upon which liberal society is founded. Furthermore, Foucault would disagree with how Schmitt describes the sovereign power to decide a state of exception, arguing that responses to crises occur along a multitude of vectors of control across various governmental and societal systems rather than through the direct power and authority of an isolated sovereign. In addition, where Schmitt observes a contradiction between the principles of legal norms in liberal democracy and the necessary actions a government must take in a time of crisis, Foucault views the law as a tool or function of governmentality which is constructed to be exploited and molded to suit the needs of the powers that be. Rather than contradict them, therefore, the authoritarian actions a liberal government might undertake under the pretext of an emergency is made possible and upheld because of the way legal norms are constructed, particularly, to allow the state to grant or take away political life from its citizenry. That is to say, it is the constant threat of crisis, be it from terror or pandemics, which justify the logics of securitization and medicalization in modern society; thus, law exists within a perpetual state of exception, and through the desensitization of the constant suspension of laws the exception becomes the norm, which functions to facilitate the state’s exercising of its biopower.

References

Agamben, Giorgio, State of Exception, (2005), trans. Kevin Attell, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2005.

France, Anatole, The Red Lily, (1894), trans. David Widger, Project Gutenberg eBook, 2006.

Foucault, Michel, Society Must Be Defended, Lecture 11, (1976), trans. By David Macey, New York, Picador, 2003.

Schmitt, Carl, Political Theology. Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty (1922), trans. by G. Schwab, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2005.